The visit of the exhibition ‘I am Gong’ by Dora Budor in the Kunsthalle Basel was a surprise. At first, it just seemed quite ordinary. A beautiful sequence of works, quite appropriate to the high standards of the Kunsthalle Basel, but nothing exceptional. During the visit, only gradually a suggestive power unfolded, a sensual intellectual seduction and enchantment, which, during later reverberations and reflections, made it clear that the entire structure of the exhibition as a sensual space had been conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk. It became clear that beyond the individual works, ‘I am Gong’ as a whole can be read as a complex work of art.

In the first contribution to ‘We Talk’ on ‘Fragments’ by Rayyane Tabet at the Carré d’Art in Nîmes, I had addressed a certain attitude or positioning towards reality as an important criterion for the quality of contemporary art. This sounds like a spongy and unclear formulation. A more elaborate analyses would be required, precisely because, in contemporary art, we are dealing mainly with objects that have their place in the world of luxury goods and of aestheticized and intellectualized consumption. Goods, which must compete for media resonance. The idea that their quality, as art, lies in a particular reflective positioning towards reality as a social, political and conceptual construct seems obvious. However, it remains vague and profusely naïve if it fails to figure out what makes this positioning specific.

In the past two years I have had several times the opportunity to visit the so-called ‘Block Beuys’, the seven-room installation by Joseph Beuys in the Hessian State Museum Darmstadt. This completely incomprehensible ensemble is and remains simply impressive. It is a grandiose artistic legacy that, through the provocative intelligence of its arrangement and its hermetic beauty, hints beyond the pure objectivity to the artist himself. The objects are turned off rather than exposed. The block refers to the procedural aspect of every successful work of art. It refers to the attitude and the philosophy of life, ultimately to the image that an artist makes him- or herself of the world and the role of humankind in it. The artwork in its visual and factual objectivity is one thing. But perhaps it cannot be so easily separated from the philosophical ethical attitude of the artist to the world when it comes to its evaluation and appraisal.

‘I am Gong’ conveyed a similar impression as the ‘Block Beuys’. While this gives a clear indication of the absence of the artist as the focal point of the intentions and power of the work, Dora Budor succeeds in turning this performative and intentional aspect away from the person to external reality. The reality out there, outside of art, and external processes are integrated to have influence on form and the sensible perception of the artwork.

Perhaps we could say that it is the working method and the approach of the artist that unfolds the bases for the criteria of good art. The working method refers to the handling of reality. It gives hints to the relation to the world as a whole. The artwork conveys this attitude as a result of the work process. It’s like a wine that can reveal everything about its location, production and the philosophy of the wine maker.

Solo for 1872, 2019 – Installation view Kunsthalle Basel

Let’s go through some parts of the exhibition again, to understand how not only attitudes become form but also reality.

The first impression does not differ much from the usual exhibitions of contemporary art. Wall objects, a sculptural ensemble, emptiness and a room-filling installation are presented in the five rooms. The superficial view could quickly conclude that it is appropriate, indeed. After all, it is the Kunsthalle Basel, a renowned institution, an important step for the promise of a career in the art world.

In the first space there are three brass plates on the walls, whose surfaces were treated chemically or electrochemically and inevitably evoke an association with Andy Warhol’s ‘Oxidation Paintings’. There are another five seating elements from the 1970s, which are partially covered by blackish gray ash. In the next room there is a piece of old parquet floor, which is fraught with some mucus in some places. Then follows an empty room with a dull red carpet.

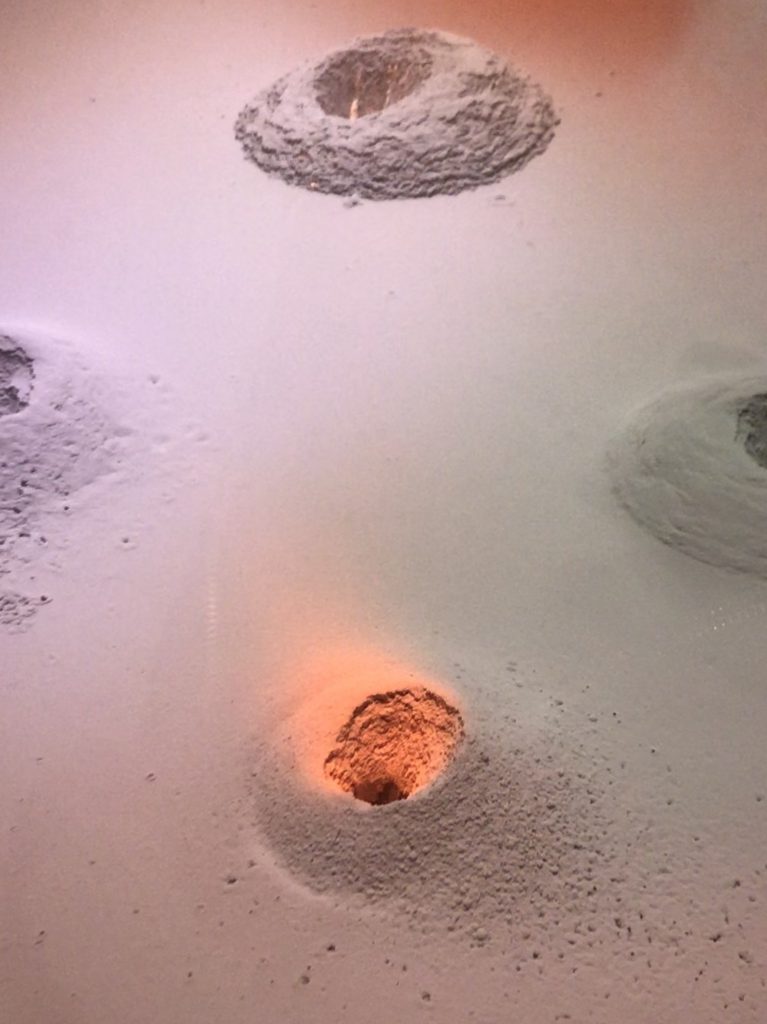

The fourth room contains three showcases that could have come from a natural history museum. It is a kind of terrarium for hobby volcanologists. In the miniature landscapes of fine sand or dust staged there, air blowers from time to time cause small volcanoes to erupt and sandstorms arise.

It’s a lovely setting that reminds me of one of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s illustrations for ‘Le Petit Prince’. It shows the little prince how he fosters and sweeps the volcanoes on his planet. In addition, the sentence from this narrative comes to mind. ‘One sees clearly only with the heart. The essential is invisible to the eyes.’

‘On ne voit bien qu’avec le coeur. L’essentiel is invisible pour les yeux.’

All this could be sufficient for a reasonable art exhibition.

In the last hall, rubble and fragments of architectural pieces are stored behind transparent tarpaulins in pale, yellowish light. Occasionally, a small remote-controlled mechanical bird flies over this eschatological landscape.

Only gradually when going out, I become aware of the soundscape in the exhibition rooms. The whole Kunsthalle is filled with noises. Sometimes they are physically felt as low frequencies, rather subliminal like inside a musical instrument. Astonished, I return to the first room. I start to listen more carefully. The sounds become more identifiable. Is it construction noise from outside on the street? Do the exhibition spaces breathe in the sound and the beat of the outside world?

As if awakened from the professional exhibition visit routine, I go back and forth, seeing ashes trickling down onto one of the design furniture arrangements. The sculptural ensemble is changing. It is not completed. It takes me a while to realize that many objects in the exhibition are constantly changing and altering their form. Automated, program-controlled processes cause the ashes to trickle down, the small flying robot to circle around and the volcanic dust to erupt. The Croatian artist, who lives in New York, has established the basic arrangement and then leaves it to mechanized, performative processes. The artworks are in a different state from moment to moment. It never ends, never has a solid closed form. Even the void is made up of sounds. A reactive sound system is installed in the cavities behind and between the walls. It turns the Kunsthalle into a sound space. The exhibition itself is subject to a performative development.

Installation view Kunsthalle Basel

‘I am Gong’ is also designed as a finely branched nervous system, which receives its impulses from the historical and architectural neighborhood of the Kunsthalle. It was completed in 1872 according to the plans of the architect Johann Jakob Stehlin-Burckhardt. Four years later, a few hundred meters away, the Basel Musiksaal was completed, designed also by Stehlin-Burckhardt. The mechanical bird flies to directional vectors, which were developed from the score of the piece, which was first performed there in 1876. The Musiksaal itself, which is one of the most acoustically outstanding music halls in Europe, functions as an orchestra for part of the exhibition. However, the microphones installed there record no concert performance, but the current noise of a construction site. The Musiksaal is currently being restored under the direction of Herzog & de Meuron. Certain intensities are transferred to the exhibition rooms and control the ejection of the ashes. ‘I am Gong’ is simply, that is slowly becoming clear, terrific, an outstanding exhibition.

And then it flashes on, that, which refers to the aforementioned ‘Block Beuys’. The approach of the so-called ‘social plastic’. The understanding of society and the construct of social, economic and ethical reality as a sculpture. I get the impression that contemporary art should also deal with the present. Art should not be afraid to get the hands dirty and open to the changes and adaptations provoked by this present. The mantras of the art world are increasingly losing their power and effectiveness. Sharpening perception, perceiving the world differently and more differentiated, highlighting the overlooked and the marginalized, all such and similar assertions about the power of art, are proving to be empty slogans in the marketplace, which seem to correspond to a marketing strategy and pretend content as a surrogate.

Only when the art of the present has proven its importance for today’s questions, feelings, hopes and fears, will it have a long-term continuance and preserve its historical value. The market and the price of a piece of art cannot replace this process.

Installation view Kunsthalle Basel

It is the outstanding quality of the exhibition, not only to provoke these questions, but to show an elegantly and aesthetically fascinating solution. How this could work, the ‘going out’ into reality. Perhaps that is one of the criteria of outstanding contemporary art? To network, connect and enter into a dialogue with reality? No cloud cuckoo land, no ivory tower, no autonomous art, or more precisely, a completely different autonomy. Such art has a firm foothold in reality and a value regardless of the market. It does not suggest lasting issues but discovers change, the transformation of reality, the urgently needed reconstruction of the world.

Dora Budor – I am Gong

Kunsthalle Basel

24.05. – 11.08.2019